Illustration courtesy of IMS Senior Graphic Designer John Ilg

The human brain is extraordinary, but it is limited in how much information it can process. Our minds simply cannot handle the effort necessary to take in everything we see, hear, or read.

Because of this, we’re often influenced by cognitive biases when processing information and making decisions—even crucial ones. Although research has shown that the brain will put forth great effort in especially important situations, cognitive biases are still likely to play a part.

So, as we continue with our discussion of improving negotiation outcomes, it is worth examining how psychological biases can both hinder and help our efforts. (Refer to Part 1 for tips on negotiation planning and strategy.)

Psychological Tools to Use in Negotiation

There are many cognitive biases that can impact negotiations, but there are three particularly significant biases that can influence the counterparty—or yourself:

- Anchoring & Adjustment

- Loss Aversion

- Risk Aversion

1. Anchoring & Adjustment

What It Is

This is an effect whereby a person bases his or her decisions and responses on an initial value. That is, the person will consider one number (called the “anchor”) as a reference point, and then adjust up or down from that number as needed to arrive at a more accurate/appealing decision.

The problem is that the influence of the initial anchor is often so strong that the adjustment is insufficient—the decision becomes biased due to the first number considered. It’s the very same effect plaintiffs often try to leverage at trial, making extreme damages requests to anchor jurors to higher damages than they might otherwise award.

This effect can happen consciously or unconsciously, whether you’re an expert or not.

In one study, judges were given a short description of a criminal case and the defendant’s conduct. Before deciding on how long to sentence him to jail, they rolled dice; unbeknownst to them, the dice were loaded such that they could only roll a three or a nine. Amazingly, the judges who rolled a three sentenced the defendant, on average, to five months in jail, while the judges who rolled a nine averaged an eight-month sentence.1 Something as simple as the numbers appearing on dice influenced how long judges sentenced someone to jail!

Even for people with specific training in negotiations, anchoring can have a robust effect.

In another study, MBA students had to negotiate the price of a car. Half were buyers and the other half were sellers. The buyers were told to minimize the cost and that they couldn’t spend more than $7,000 on the car, and the sellers were told to maximize the profit and couldn’t sell for less than $2,500. Results showed that for every $100 added to the seller’s initial ask, the final agreement increased by an average of $28, and for every $100 reduced from the buyer’s initial bid, the agreement decreased by an average of $15.2

How to Use It

For the purposes of your own negotiations, this is another reason why it’s beneficial to start with an initial offer that’s lower than your end goal. Think back to the example near the end of Part 1—it showed that if you make an offer of $280,000, the plaintiff’s counter might be $380,000, but if you instead make an offer of $220,000, the counter might be $360,000. That’s because of the influence of your anchor.

And what about when your opponent sets an extremely high anchor? One option you have is to quickly give a counteroffer so that the anchor isn’t on everyone’s minds for much time. Taking time to mull it over just allows the initial anchor to become more influential. Another option is to decline altogether and tell them to come back with a realistic demand. This way, the counterparty is forced to set a new, lower anchor, which should essentially remove the effect of the first anchor.

2. Loss Aversion

What It Is

The last two biases (loss aversion and risk aversion) highlight the importance of reminding the plaintiff about the cost of forgoing a settlement and risking going to trial.

People dislike thinking about losses, so they try to avoid it. They dislike it so much that they give losses too much weight when making decisions. That is, people are generally more influenced by avoiding potential losses than seeking potential gains.

A 1991 study showed that when subjects were asked how much of their own money they would pay for a coffee mug, the average response was around $3. However, when subjects were given that same coffee mug and asked how much money they would need to be given to sell it, the average amount was around $7.3 It’s the exact same mug, and yet the first group devalued it in light of the money they would lose to buy it, while the second group perceived its value to be higher in light of the possibility of losing it.

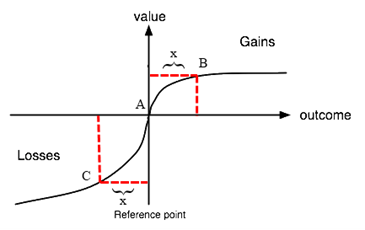

Ultimately, as the graph below4 depicts, the unhappiness we receive from a loss is larger than the happiness we receive from an equivalent gain. This is why free trial periods are an effective marketing tactic; once people think about a good or service or as something they possess, they don’t like to lose it.

How to Use It

This bias has the potential to be harmful to the defense when trying to reach a settlement. The defense wants to negotiate down to a lower value, which can easily be perceived by the plaintiff as a loss. However, there are ways you can frame your offer as a gain instead.

For example, “That is a bit high, but what I can give you is….” The perceived gain can then be reinforced by describing what that money can pay for: the plaintiff’s medical bills, their child’s college, investments, etc. This will keep the plaintiff’s focus on what they are gaining (rather than losing) by accepting a lower offer.

Another way the defense can use this heuristic in negotiations is to talk about what the plaintiff could “lose” if an agreement isn’t reached. Attention can be put on a failed negotiation and what it means—that the plaintiff risks losing X amount of dollars and ending up with nothing.

You can reinforce this point by talking about the settlement as “cash-in-hand,” and emphasizing that if the plaintiff walks away from the deal, they walk away with nothing in hand. (Such a tactic leverages another psychological principle called temporal discounting: Most people would rather have something now than wait for something greater.)

Finally, remind the plaintiff of the potential to invest the settlement money immediately, and contrast it with just how long they might have to wait if they go to trial (e.g., when the trial will start, the length of the trial, and the possibility for appeals even if the plaintiff wins).

3. Risk Aversion

What It Is

Similar to loss aversion, most people like to avoid risks to the point where it biases their decision making. Specifically, people give too much weight to small risks when reaching decisions. People will generally choose a definite outcome with a smaller reward than a higher reward that involves a risk. (A bird in the hand really is worth two in the bush.)

For example, one study showed that the vast majority of subjects would rather have a guaranteed $50 than a 50% chance of getting $100. The two have equivalent expected payoffs, so from a rationality perspective, there shouldn’t be a preference—and yet this effect has been shown to exist even when the guaranteed outcome has a smaller expected value than the risky option.5

How to Use It

Risk aversion is a good thing for defendants in negotiations. The plaintiff wants a gain, and they will be more willing to take a smaller, certain gain than a larger, risky gain: i.e., a trial. As Daniel Kahneman (the only psychologist to ever win a Nobel Prize in Economics, awarded for his research on these heuristics) said, “The superior bargaining position of the defendant should be reflected in negotiated settlements, with the plaintiff settling for less than the statistically expected outcome of the trial.”6

This is because plaintiffs will often take less money if it means a guaranteed outcome. So, when negotiating as the defense, you can highlight to plaintiffs that they risk ending up with nothing if an agreement isn’t reached.

Trying to get a sense for how risk averse a specific plaintiff tends to be is also helpful. While research suggests certain demographics are more risk averse on average,7 it’s also possible to infer someone’s level of risk aversion based on what is known about them—if they have planned well for retirement, for instance, they are likely more risk averse. If they do extreme sports or ride a motorcycle, they may be less risk averse. Such insights can affect your offers and strategies accordingly.

Final Thoughts

There are many cognitive biases that affect negotiations, but the three described above are some of the most influential.

Overall, you should be aware of the anchoring power of the first number offered in negotiations and remind the plaintiff of the risks and potential losses involved if they keep holding out for a better deal—compared to the certain gains they could have immediately upon settling.

The final part of this series offers techniques for communicating effectively with your opponent and ensuring you’re sending the desired signals.

References

1 Englich, B., Mussweiler, T., & Strack, F. (2006). Playing dice with criminal sentences: The influence of irrelevant anchors on experts’ judicial decision making. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(2), 188-200.

2 Raiffa, H., Richardson, J., & Metcalfe, D. (2002). Negotiation analysis: The science and art of collabora-tive decision making. Harvard University Press.

3 Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic perspectives, 5(1), 193-206.

4 Gearon, M. (2018, October 15). Cognitive biases: Loss aversion. Retrieved from: https://uxdesign.cc/cognitive-biases-loss-aversion-925149360f46

5 Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

6 Ibid.

7 Halek, M. & Eisenhauer, J. (2001). Demography and risk aversion. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 68(1), 1-24.